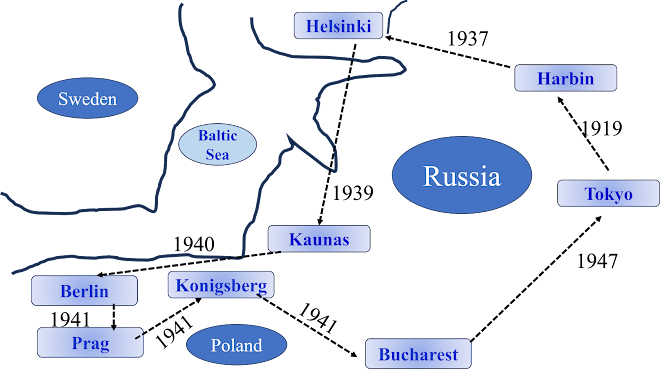

Sugihara Chiune: A Japanese Holocaust Rescuer

Fig.

Sugihara Chiune

This is a schematic picture. The innterested reader can visit the following wikipedia site for real image:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e8/Sugihara_b.jpg

In the 1980’s I often went to America to attend technical conferences. In one of those occasions, my flight to Tokyo was the next day after the conference was over. In order to kill my time, I went to a nearby little library where I saw a book with title “The Sugihara Story”. Since then this name never left my head.

Diplomatic Path and Humanitarian Compassion

The Miracle of Visas

In defiance of official instructions from Tokyo, Sugihara took it upon himself to issue 2139 transit visas [2] -[5] to Jewish refugees, allowing them to travel through Japan to safe places. Since each visa was valid for its family members, it is estimated that 6000 people were saved. Sugihara's audacious decision to go against protocol and offer aid to the persecuted was not merely an act of defiance; it was a courageous stand against injustice.

Fig. Visa Sugihara Issued. This is a schematic picture. Interested reader can visit the following for the real image at wikimedia:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Transit_visa.jpg

Day and night, Sugihara tirelessly wrote visas, driven by his conviction that helping those in need was a responsibility he could not shirk. His right hand started aching such that his wife had give him a massage [6]. He didn't eat lunch and his face started sinking. Despite the imminent threat of consequences from the Nazis, Soviet threat and Japanese authorities, Sugihara chose humanity over bureaucracy.

He had several outstanding capabilities to solve complex problems in a short period of time. I will describe them in my other blogposts.

Legacy of Selflessness

Sugihara's

actions were not solely rooted in empathy but also in a deep moral clarity. He

once said, "I did nothing special. I did what is right." This

sentiment encapsulates his humility and his belief in the fundamental duty of

every human being to stand up for the vulnerable, regardless of the personal

cost.

After the war, he was forced to retire. In 1985, however, Sugihara was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. This title is bestowed upon non-Jewish individuals who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. Sugihara's selfless actions echoed the deeds of Oskar Schindler and Raoul Wallenberg, reminding the world that even in times of darkness, there are individuals who shine as beacons of hope.

Conclusion

Sugihara's story transcends national

borders, cultures, and languages. He was not just a diplomat; he was a

humanitarian who acted with extraordinary ability to solve complex problems and

courage to alleviate human suffering. His legacy serves as a timeless reminder

that a single individual, driven by compassion and guided by a sense of

justice, can make an indelible mark on history. It would be difficult to find

an incident in the human history where a single individual saved 6000 lives. Sugihara's

life teaches us that even when faced with overwhelming challenges, our actions

have the power to change lives, inspire generations, and remind us of the

inherent goodness that exists within humanity. I will explore details of his

achievements in other blog posts.

[1] Youtube site:

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=Chiune+Sugihara+Doc.+1

[2] Altman, I., “The Soviet Union and

the Transit of Jewish Refugees, 1939–1941”, in Sugihara Chiune and the Soviet

Union: New Documents, New Perspectives, Slavic-Eurasian Research Center,

Hokkaido University, 2022

[3] Wolff, D.,

“Phoney War, Phoney Peace: Sugihara’s Shifting Eurasian Context”, in Sugihara

Chiune and the Soviet Union: New Documents, New Perspectives, Slavic-Eurasian

Research Center, Hokkaido University, 2022

[4] Ishigo-oka, K., “Sugihara Chiune

and Stalin” , Gogatshu Shobo, Tokyo, 2022.

[5] Watanabe, K., “Ketsudan: Visas for

Life”, Taisho Shuppan, Tokyo, Third Printing, 2001

Comments

Post a Comment